Archives

When two worlds collide!

In the domain of folk music, Rewben Mashangva is a name that hardly needs an introduction. This wandering minstrel, belonging to the Tangkhul Naga community has been serenading about the joys and travails of the simple people of his community in his trademark folksy-blues fashion, resulting in the creation of an entirely new musical genre called the Naga Folk Blues. In his film, Doren shows how Rewben travels through the remote villages of the Tangkhul Nagas in the hills of Manipur to talk to the old people and collect their instruments. “He links the traditional melodies, rhythms and lyrics with his own Blues music and uses it to spread the message that there is no reason to be ashamed of one’s own culture.”

The music Rewben plays is called HAO music, derived from the name of the community before it was changed by the British. The main instruments he uses while performing are the ‘Tingtelia’, a traditional violin type instrument, which took him 7 years to modify to suit his needs, and the Yankahuii - a long traditional bamboo flute which he has now modified to be more consistent tonally. The acoustic guitar and harmonica are the other two instruments Rewben uses a lot. His son Saka, donning the traditional hairdo called Haokuirut like his father, usually accompanies him with cowbells.

The music Rewben plays is called HAO music, derived from the name of the community before it was changed by the British. The main instruments he uses while performing are the ‘Tingtelia’, a traditional violin type instrument, which took him 7 years to modify to suit his needs, and the Yankahuii - a long traditional bamboo flute which he has now modified to be more consistent tonally. The acoustic guitar and harmonica are the other two instruments Rewben uses a lot. His son Saka, donning the traditional hairdo called Haokuirut like his father, usually accompanies him with cowbells.

Producing the script and content of a film like this on the cultural traditions of the people in the hills is a tough proposition, primarily due to the absence of any written history in place as almost all the tribes in Northeast India depended more on oral communication in the days of yore. The death of most of the elders in the tribal societies has also compounded matters further. Doren says, “The elders who are still alive are either too old to speak or settled in some remote corner which is inaccessible by modern day roads and communication forms. Moreover, no books or recordings of folk songs are available in the market or in libraries that we know of. So basically it was very raw first hand data and song recordings we collected in the process of our production.”

The filmmaking team did have some written evidence about the inroads of Christianity in the hills. We got second hand information about the arrival of Christian missionary William Petigrew in Ukhrul district in 1896 from the sons of those who studied under the reverend. We were also lucky to find a book in a Christian literature outlet ‘Forty years mission in Manipur – mission reports of Rev. William Pettigrew’ in which the reverend has written in detail about his experience with the natives, i.e. the Tangkhul Nagas.”

Watching Rewben traverse the exotic landscapes amidst the lush greenery, the old Tangkhul elders singing folktales to each other while sipping rice beer besides the fireplace, women pounding rice in the traditional method and other such details, in the nostalgic rides of the director, truly proves to be a cinematic delight. The ‘dreamy-nostalgic’ sequence also has dangerous honey bees walking up and down a path, buffalo heads hung in front of old houses, crafted wooden tribal motifs in the facade of the old traditional house ‘haosym’, depicting the order of the relationship between the Tangkhul- Nagas and other living organisms, trees, mountains etc.

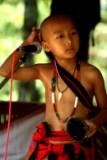

Songs of Mashangva was shot for more than a year in different locales of Northeast India, including Shillong, Imphal, Nagaland and a number of villages in Ukhrul and Chandel district of Manipur, as also in Kolkata, Rajasthan and New Delhi. The filmmaker, Oinam Doren, is a former TV producer who left his job to pursue his passions of filmmaking and culture. Having won the Tata Fellowship in 2010 to research Angami folk music, Doren is presently developing an international feature film project, Little Lama, with the support of the Goteborg International Film Fest. Songs of Mashangva will also be screened in the Almaty International Film Festival in Kazakhstan next month.

Ayushman Dutta