A couple from Pune, in their mid 50s - one an accomplished agricultural scientist with over 30 years of field experience and his wife, a committed educationist - have been living in Aben, an extremely remote village, for almost 2 and half year in Manipur’s most backward district, Tamenglong, studying the impact of Jhum cultivation on the lives of the Zeme tribe, who inhabit the village to counter the challenges that the hill people of region are facing by offering an viable alternative cultivation, a climate-change smart sustainable method of agriculture.

Sloping Agriculture Land Technology or Small Agro-Livestock Land Technology or SALT in short, is what the couple is successfully introducing in the village with encouraging results, leading to increasing the productivity of the hill farmers and enhancing their income by introducing integrated system of farming.

Aben is tucked so far away, untouched by modern civilization and villagers rely primarily on shifting or jhum cultivation and the forest for their sustenance. With the region receiving eight months of rain in a year and given the pathetic conditions of the inter-village roads, 4×4 vehicle or foot is the only means of communication to Aben during monsoon.

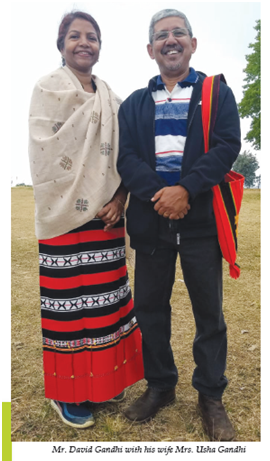

Given this circumstance, the commitment showed by David and Usha Gandhi, staying in the remote with the community, depriving themselves from even the basic amenities of modern existence, living in a small tin cabin and mostly without electricity, all this to offer a better lifestyle for villagers by coming a practice and sustainable form of cultivation amidst the global climate crisis is indeed inspirational. Eastern Panorama’s writer Sunzu Bachaspatimayum caught up with the Man on the Mission to understand his amazing crusade and methods for solving the challenges of the people.

Given this circumstance, the commitment showed by David and Usha Gandhi, staying in the remote with the community, depriving themselves from even the basic amenities of modern existence, living in a small tin cabin and mostly without electricity, all this to offer a better lifestyle for villagers by coming a practice and sustainable form of cultivation amidst the global climate crisis is indeed inspirational. Eastern Panorama’s writer Sunzu Bachaspatimayum caught up with the Man on the Mission to understand his amazing crusade and methods for solving the challenges of the people.

1. SB: Tell us about yourself and your wife and share what made you come to Manipur and work in the village of Aben.

DG: Thanks, Sunzu for your interest in our work. My wife and I have spent a lot of time in rural areas of India and are aware of and concerned about the issues faced by the people living there. My work in the rural development sector has taken me across the length and breadth of the country, requiring me to stay with my family in many a small town and village. Our home is in Pune city, Maharashtra and in mid-2016, we traveled to the North East region where I was invited by an NGO, the Rongmei Naga Baptist Association (RNBA) to be a team member for an assessment of their rural development activities in Manipur and Nagaland. Travelling among these beautiful mountains and valleys and meeting the vibrant tribal communities was a fascinating experience, and yet my mind was confused as to what could be the solutions to the challenges faced by the people. I realized that in order to find answers, I would have to closely interact with the people and study their livelihoods first hand. Of all the areas we visited, Aben village appealed to me the most. Given the remote location, commuting to and fro was not a practical option. My wife was of the same opinion and hence I requested the village leadership for permission to make a home in Aben in order to live and work with them.

Please share your experiences of living in the remote community in Aben and what have you understood about their agricultural practices and challenges they are facing and how are you helping them find practical and sustainable solutions.

DG: We moved to Aben in Oct 2016 and settled into a small wood and bamboo cabin built for us by the community. Living with the Zeme Naga community has been an amazing experience. We have witnessed firsthand how good natured and resilient they are, living without basic facilities like dependable power supply, water supply, health clinic, education, motorable roads, market, bank, post office and so many other conveniences which we in the cities and developed areas of the country take for granted. The community has been very welcoming and willing to share their meagre resources with us. We have a small solar unit for power supply and collect rainwater from the roof. We eat the food grown in the jhum (shifting cultivation /slash and burn agriculture) fields. I work on agriculture and natural resource management issues while my wife works to improve the quality of education at the school in Aben and other villages. We keep a small supply of essential medicines for our own use and to share with those in need. We both are in our mid-fifties and in good health and with God’s grace have not faced any major problem during our stay here.

Coming to the subject of Agriculture, the main livelihood of the people is from jhum cultivation. This is an ancient system of subsistence farming, wherein each year a patch of surrounding jungle is manually cleared of vegetation, which is allowed to dry in the sun and then set afire. With the onset of the rains, seeds of upland rice, millets, maize, hill vegetables are sown directly into the ashes, which provide the nutrients for plant growth. The people are occupied over the next 3-4 months in weeding the fields otherwise the crop will be suffocated by bamboo and thatch. This is a very difficult job, which involves trudging to the distant fields along treacherous mountain paths, working full day in the rain and sun getting bitten by numerous insects and leeches. During this period, bamboo shoot is the main source of food for the people. Harvest beginning September onwards is a time of rejoicing and the people look forward to having sufficient food till the next year. Sadly this is not the case. Yields from the jhum fields have been declining in recent years and we have observed that by December itself many families have run out of rice to eat and are going to the jungle searching for edible leaves, mushrooms, roots and tubers.

Reasons for decline in jhum production are many. Foremost of course is the weakening of the natural resource base. The land has lost its capacity to sustain the crops as a result of soil erosion. Earlier there used to be wood to burn for ashes to provide nutrients, now there are only hollow bamboo stems. The sloping land cannot hold the rainwater and the soil dries easily. On these degraded slopes, the crops cannot compete with the weeds, which grow rapidly, and the women are hard pressed to keep up with weeding. There are social reasons as well. Jhum farmers are mainly elderly people, since most of the younger generation has left the villages for education or employment in the cities. Hence, the labor is not sufficient to maintain the jhum fields and many are neglected or abandoned after sowing. Another important reason is that today we have a cash economy – jhum being a system of subsistence farming does not generate cash income. Hence, the younger generation prefers to migrate to cities for employment. This is leading to weakening of the tribal society and culture.

Sunzu Bachaspatimayum

To read the further articles please get your copy of Eastern Panorama April issue @http://www.magzter.com/IN/Hill-Publications/Eastern-Panorama/News/ or mail to contact @easternpanorama.in