A very significant observation is made by Ranjit S Mooshary, former Governor of Meghalaya, in his foreword to the book, "Social Cultural And Spiritual Traditions of North East Bharat (Published by Heritage Foundation, Guwahati)". He points out quite pertinently that "There is no other region which mirrors India's heterogeneous heritage as the Bramhaputra valley and its hemming hills". It is indeed cent percent true. There is no denying that the North East offers a fascinating mosaic of beliefs, customs and dialects. Their life is peaceful and contentment seems to spill out in their thoughts and behaviours.

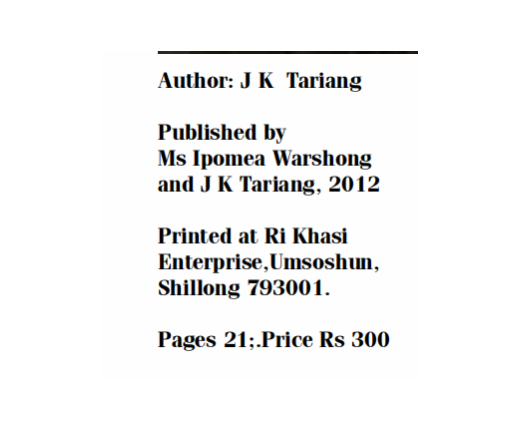

Inspired by the same spirit of probing the cultural and religious diversity, J K Tariang has successfully expostulated the indigenous religion of his people mainly residing in the East and West Khasi Hills of Meghalaya. In his book, the writer has brilliantly defined what exactly is meant by their religion and how the various forces and factors contribute to the vibrant growth of Niam Khasi. In fact he has 'dexterously analysed, rationalised and systematised almost all the folklores and myths associated with the Khasi religion."These values and customs are deftly filtered with a view to making these a vital part of the life of a millennial Khasi.

Inspired by the same spirit of probing the cultural and religious diversity, J K Tariang has successfully expostulated the indigenous religion of his people mainly residing in the East and West Khasi Hills of Meghalaya. In his book, the writer has brilliantly defined what exactly is meant by their religion and how the various forces and factors contribute to the vibrant growth of Niam Khasi. In fact he has 'dexterously analysed, rationalised and systematised almost all the folklores and myths associated with the Khasi religion."These values and customs are deftly filtered with a view to making these a vital part of the life of a millennial Khasi.

Meghalaya has three main tribes, the Khasis, the Jaintias and the Garos. The Garos are mostly to be found in the Garo Hills and are from a Tibetan Burmese group called Achik Mande. The Khasis inhabit the Khasi Hills both the  east and the west .The Jaintias are mainly from the Jaintia Hills. Today none of these tribes live in isolated habitations rather they can be found everywhere including in the various states of the North East. The Jaintias too claim to be from Ki Hinniew, the Jayantia Kingdom belonged to what was called Synteng community. They are also addressed as Pnars and their religion is Niam tre.They too subscribe to the belief that their religion has come by God's decree. In this book, the author elaborately discusses what constitutes Niam Khasi and underpins its main features as well as its essence. The writer clearly mentions that these terms Seng Khasi and Sengraj do not exactly refer to their religions.

east and the west .The Jaintias are mainly from the Jaintia Hills. Today none of these tribes live in isolated habitations rather they can be found everywhere including in the various states of the North East. The Jaintias too claim to be from Ki Hinniew, the Jayantia Kingdom belonged to what was called Synteng community. They are also addressed as Pnars and their religion is Niam tre.They too subscribe to the belief that their religion has come by God's decree. In this book, the author elaborately discusses what constitutes Niam Khasi and underpins its main features as well as its essence. The writer clearly mentions that these terms Seng Khasi and Sengraj do not exactly refer to their religions.

The book has 11 chapters and each chapter presents an interesting comingling of the past and the present, a beautiful fusion of the synchronic and the diachronic. It does provide an interesting cognitive excursion to the reader while the entire gamut of their religion binds the different sections with an invisible thread creating a kind of an organic unity. At the end of each chapter references are given providing credible authenticity to the book.

The first chapter of the book is "introduction" and it faithfully performs its function more than what the first act of a Shakespearean tragedy does.

To read the further articles please get your copy of Eastern Panorama June issue @http://www.magzter.com/IN/Hill-Publications/Eastern-Panorama/News/ or mail to contact @easternpanorama.in