Seasonal migration for work is a pervasive reality in rural India. An overwhelming 120 million people or more are estimated to migrate from rural areas to urban labour markets, industries and farms. Migration has become essential for people from regions that face frequent shortages of rainfall or suffer floods, or where population densities are high in relation to land. Areas facing unresolved social or political conflicts also become prone to migration. Poverty, lack of local options and the availability of work elsewhere have become the trigger and the pull for rural migration respectively.

Some regions like UP and Bihar have been known for rural migration for decades – however, newer corridors like Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and recently even North East have become major sending regions of manual labour. Among the biggest employers of migrant workers is the construction sector (40 million), domestic work (20 million), textile (11 million), brick kiln work (10 million), transportation, mines & quarries and agriculture.

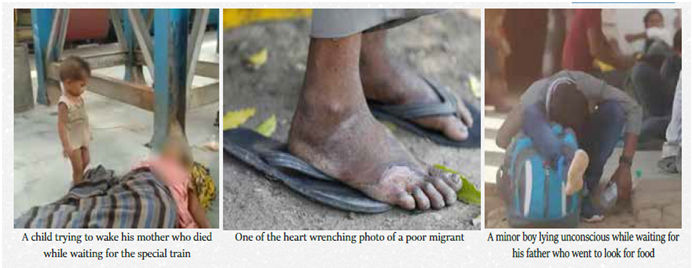

Devoid of critical skills, information and bargaining power, migrant workers often get caught in exploitative labour arrangements that forces them to work in low-end, low-value, hazardous work. Lack of identity and legal protection accentuates this problem. The hardships of migrant workers are especially magnified when state boundaries are crossed and the distance between the "source" and "destination" increases. Migrants also become easy victims of identity politics and parochialism.

Despite the vast number of migrant workers, the policies of the Indian state have largely failed in providing any form of legal or social protection to this vulnerable group. The urban labour markets treat them with opportunistic indifference extracting hard labour but denying basic entitlements such as decent shelter, fair priced food, subsidized healthcare facilities or training and education. They are also usually out of bounds of government and civil society initiatives, both because of being "invisible" and for their inability to carry entitlements along as they move.

Population of Migrants in India

The total number of internal migrants in India, as per the 2011 census, is 45.36 crore or 37% of the country’s population. This includes inter-state migrants as well as migrants within each state, while the recent exodus is largely due to the movement of inter-state migrants.

The annual net flows amount to about 1 per cent of the working age population. As per Census 2011, the size of the workforce was 48.2 crore people. This figure is estimated to have exceeded 50 crore in 2016 — the Economic Survey pegged the size of the migrant workforce at roughly 20 per cent or over 10 crore in 2016. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are the biggest source states, followed closely by Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, Jammu and Kashmir and West Bengal; the major destination states are Delhi, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala.

Contribution towards Economy

Governments in India clearly have no systematic understanding of their existence and had not anticipated the scale of the migrant exodus. The crisis should spur the government to collect better data and work closely with other stakeholders who have their ear to the ground. A number of empirical studies which indicated that the major sub-sectors using migrant labour are textiles, construction, stone quarries and mines, brick-kilns, small-scale industry (diamond cutting, leather accessories, etc.), crop transplanting, sugarcane cutting, rickshaw-pulling, fish and prawn processing, salt panning, domestic work, security services, sex work, small hotels and roadside restaurants/tea shops and street vending. The calculations based on these estimates indicate that the economic contribution of migrants is around 10% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The law of labour commission

Whose job is it to think of migrant workers, who migrate from their home states to other states for work? Whose responsibility should it have been to organize transport for them to have returned home with safety and precautions to prevent transmission? Is it the state government’s responsibility, or the Centre? Is it the responsibility of the sending state – where these migrants’ homes are, or the responsibility of the receiving state – where they work? Who should have taken the initiative to mobilize the workers, organize them, prepared for logistics and helped them return?

India has an existing legislation, The Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979, which has been one of the most poorly implemented legislations in the country. While the legislation has some good provisions on how the labor departments of each state can monitor and ensure protection from abuse and exploitation of migrants who are recruited, transported and supplied to employers in the unorganized labor sectors, the provisions have gone unimplemented for nearly 4 decades, resulting in lack of protection and safety of most vulnerable migrants in India.

Rashmi Mizar

To read the further articles please get your copy of Eastern Panorama June issue @http://www.magzter.com/IN/Hill-Publications/Eastern-Panorama/News/ or mail to contact @easternpanorama.in